Unit Fractions

A unit fraction is a fraction of the form 1/n, where n is

a positive integer . In this problem, you

will find out how rational numbers can be expressed as sums of these unit

fractions. Even if you

do not solve a problem , you may apply its result to later problems.

We say we decompose a rational number q into unit

fractions if we write q as a sum of 2 or

more distinct unit fractions. In particular, if we write q as a sum of k

distinct unit fractions, we

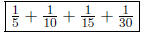

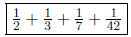

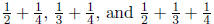

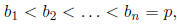

say we have decomposed q into k fractions. As an example, we can decompose 2/3

into 3 fractions:

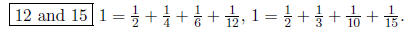

1. (a) Decompose 1 into unit fractions.

Answer:

(b) Decompose 1/4 into unit fractions.

Answer:

(c) Decompose 2/5 into unit fractions.

Answer:

2. Explain how any unit fraction 1/n can be decomposed into other unit fractions.

Answer:

3. (a) Write 1 as a sum of 4 distinct unit fractions.

Answer:

(b) Write 1 as a sum of 5 distinct unit fractions.

Answer:

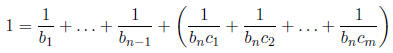

(c) Show that, for any integer k > 3, 1 can be decomposed

into k unit fractions.

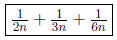

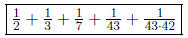

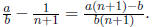

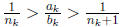

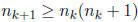

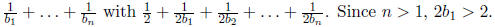

Solution : If we can do it for k fractions, simply replace the last one

(say 1/n) with

Then we can do it for k +1 fractions. So,

since we can do it for k = 3, we

Then we can do it for k +1 fractions. So,

since we can do it for k = 3, we

can do it for any k > 3.

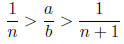

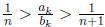

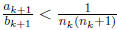

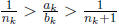

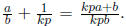

4. Say that a/b is a positive rational number in simplest

form, with a ≠ 1. Further, say that n is

an integer such that:

Show that when  is

written in simplest form, its numerator is smaller than a.

is

written in simplest form, its numerator is smaller than a.

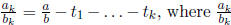

Solution:  Therefore,

when we write it in simplest form, its numerator

Therefore,

when we write it in simplest form, its numerator

will be at most a(n + 1) − b. We claim that a(n + 1) − b < a. Indeed, this is

the same as

an − b < 0 <-> an < b <-> b/a > n, which is given.

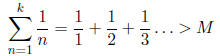

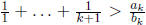

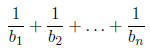

5. An aside: the sum of all the unit fractions

It is possible to show that, given any real M , there exists a positive integer k

large enough

that:

Note that this statement means that the infinite harmonic series,

grows without

grows without

bound, or diverges. For the specific example M = 5, find a value of k, not

necessarily the

smallest, such that the inequality holds . Justify your answer.

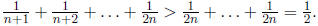

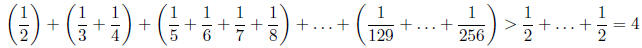

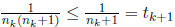

Solution: Note that

Therefore,

if we apply this

Therefore,

if we apply this

to n = 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, we get

so, adding in 1/1 , we get

so k = 256 will suffice.

6. Now, using information from problems 4 and 5, prove that the following

method to decompose

any positive rational number will always terminate:

Step 1. Start with the fraction a/b . Let t1 be the largest unit fraction 1/n

which is less than or

equal to a/b .

Step 2. If we have already chosen t1 through tk,

and if t1 +t2 +. . .+tk is still less than a/b

, then

let tk+1 be the largest unit fraction less than both tk

and a/b .

Step 3. If t1 + . . . + tk+1 equals a/b , the decomposition is found. Otherwise, repeat step 2

Why does this method never result in an infinite sequence of ti?

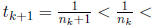

Solution: Let  is a fraction in simplest terms. Initially, this

is a fraction in simplest terms. Initially, this

algorithm will have etc. until

etc. until

This will eventually happen

This will eventually happen

by problem 5, since there exists a k such that At

that point, there is

At

that point, there is

some n with such that

such that

In this case,

In this case,

Suppose that there exists nk such that

for some k. Then we have

for some k. Then we have

and  This shows that once we have found nk

such that

This shows that once we have found nk

such that  and

and

we no longer have to worry about tk+1

being less than tk, since

we no longer have to worry about tk+1

being less than tk, since

tk, and also  while

while

On the other hand, once we have found such an nk,

the sequence {ak} must be decreasing

by problem 4. Since the ak are all integers, we eventually have to

get to 0 (as there is no

infinite decreasing sequence of positive integers). Therefore, after some finite

number of steps

the algorithm terminates with

which is what we wanted.

Juicy Numbers [100]

A juicy number is an integer j > 1 for which there is a

sequence a1 < a2 < . . . < ak of positive

integers such that ak = j and such that the sum of the reciprocals of

all the ai is 1. For example,

6 is a juicy number because  , but 2 is not

juicy.

, but 2 is not

juicy.

In this part, you will investigate some of the properties

of juicy numbers. Remember that if

you do not solve a question, you can still use its result on later questions.

1. Explain why 4 is not a juicy number.

Solution: If 4 were juicy, then we would have

The . . . can only possible contain

The . . . can only possible contain

1/2 and 1/3 , but it is clear that  are all

not equal to 1.

are all

not equal to 1.

2. It turns out that 6 is the smallest juicy integer. Find

the next two smallest juicy numbers,

and show a decomposition of 1 into unit fractions for each of these numbers. You

do not need

to prove that no smaller numbers are juicy.

Answer:

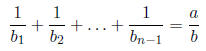

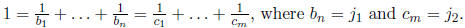

3. Let p be a prime. Given a sequence of positive integers

b1 through bn, exactly one of which

is divisible by p , show that when

is written as a fraction in lowest terms , then its

denominator is divisible by p. Use this fact

to explain why no prime p is ever juicy.

Solution: We can assume that bn is the

term divisible by p (i.e. bn = kp) since the order

of addition doesn’t matter. We can then write

where b is not divisible by p (since none of the bi

are). But then  Since b

Since b

is not divisible by p, kpa + b is not divisible by p, so we cannot remove the

factor of p from

the denominator. In particular, p cannot be juicy as 1 can be written as 1/1 ,

which has a

denominator not divisible by p, whereas being juicy means we have a sum

where  and so in particular none of the bi

with i < n are divisible by

p.

and so in particular none of the bi

with i < n are divisible by

p.

4. Show that if j is a juicy integer, then 2j is juicy as

well.

Solution: Just replace

5. Prove that the product of two juicy numbers (not

necessarily distinct) is always a juicy

number. Hint: if j1 and j2 are the two numbers, how can

you change the decompositions of

1 ending in  to make them end in

to make them end in

Solution: Let  Then

Then

and so j1j2 is juicy.

| Prev | Next |