Inverse Functions

Defining Inverse Functions

In our final lecture of the term , we discuss the concept of the inverse of a

function. Let f(x) be a real-valued

function. We say that g(x) is the inverse of f(x) if for all values of x in the

domain of f(x), we have that

g(f(x)) = x,

and for all values of x in the domain of g(x), we have that

f(g(x)) = x.

So composing g after f cancels out the action of f, and composing f after g

cancels out the action of g. We

usually denote the inverse of f(x), if it exists, by f-1(x). If f(x) is the

inverse of g(x), then g(x) is also the

inverse of f(x).

We already have an important example of inverse functions. the inverse of the

exponential function ex is

the natural logarithmic function ln x, since for all real numbers x, we have

that

and for all values of x in the domain of ln x (what is this domain?) we get that

Likewise, the functions ax and logax are inverses to each other, because we

defined logax specifically to

have this property .

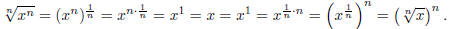

Another example of inverse functions are xn when n is a odd natural number and

the nth root function

Both of these functions are defined everywhere, and we have that

Both of these functions are defined everywhere, and we have that

This concept of inverse function gets a little more tricky

when we consider the function  when n is an

when n is an

even natural number ( like the usual square root function). The function

is always non-negative

is always non-negative

(that is, positive or 0). This restriction makes an impact on the domain of the

inverse function. we would

guess that xn would be the inverse to  and

this is true, but xn is defined for all real numbers. If x is a

and

this is true, but xn is defined for all real numbers. If x is a

negative number, then

because x is negative, but the nth root of any number is

non -negative when n is an even number. Thus

does not cancel out the action of xn when x is a negative number. The solution

is to restrict the domain

of xn to non-negative numbers, and, indeed, xn on the domain x ≥ 0 is the

inverse function of  The

The

lesson here is that we always need to be conscious of the domain of a function

as well as its formula, because

studying the formula alone can give us the wrong answer.

Some functions do not have inverse functions. for these

functions, there is no way to cancel out their

action on x, to put the machine into reverse, once that action is done. Chief

among these functions are the

constant functions f(x) = c. A constant function sends every number x to some

constant c. If g(x) were the

inverse to f(x) = c, then for every value of x we would have that

x = g(f(x)) = g(c).

So g(c) would have to have every real number as a value,

which is impossible, because as a function, g(c) can

take exactly one value and one value only. So constant functions cannot have

inverse functions. Likewise,

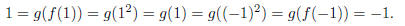

consider the function f(x) = x2 defined everywhere. If g(x) is the inverse of

f(x) = x2, then, specifically,

for x = 1 and x = -1 we would have

Thus if g(x) is the inverse function of f(x) = x2 (defined

everywhere), then both g(1) = 1 and g(1) = -1,

which is impossible if g(x) is indeed a function. So f(x) = x2 defined

everywhere does not have an inverse.

We can restrict its domain, however, as we saw in the previous paragraph , and

get a function which does

have an inverse. Why does f(x) = x2 defined everywhere not have an inverse,

while f(x) = x2 defined on

the non-negative numbers does? We examine their graphs to find out .

Graphs of Inverse Functions and the Horizontal Line Test

The graph of a function and the graph of its inverse are

related. To see this relationship, plot the graph of

ex and the graph of ln x on the same set of axes. Now plot the line y = x. What

you should see is that

the graph of ex and the graph of ln x are exact reflections of each other in the

line y = x. This is true not

just for ex and ln x, but for the graphs of f(x) and f-1(x) as well. the graph

of f-1(x), when this function

exists, is the reflection of the graph of f(x) in the line y = x.

Why is this the case? When we reflect the point (x, y) in

the line y = x, we get the point (y, x) (test this

on a few points to convince yourself of this). Every point on the graph of f(x)

is of the form (x, f(x)), so

every point in the reflection of the graph of f(x) in the line y = x is of the

form (f(x), x). If the reflection

is the graph of a function, then this function takes f(x) and sends it to x for

every x in the domain of f,

which is precisely what the inverse function is supposed to do.

Thus, knowing what the graph of x3 looks like, you should

be able to draw the graph of  , and knowing

, and knowing

how to draw the graph of x2 for x ≥ 0, you should be able to sketch the graph of

What about the constant function f(x) = c? The graph of

this function is a horizontal line. Therefore,

if we reflect the graph of f(x) = c in the line y = x, we get the vertical line

x = c. This vertical line cannot

be the graph of a function, since it obviously does not pass the vertical line

test. So this graphically justifies

why we say that constant functions do not have inverses.

What about the function f(x) = x2 defined everywhere? When

we reflect it in the line y = x, the result

is the solution curve of the relation x = y2, which is a parabola on its side.

If you sketch this solution

curve, you see that it does not pass the vertical line test either, particularly

at x = 1, as we showed before

algebraically . So f(x) = x2 defined everywhere does not have an inverse either.

These two examples give us a clue as to a test we can use

to see it a function does not have an inverse.

In both of these cases, the reflection of the graph of the function failed the

vertical line test. some vertical

line x = a passed through the reflection at two points or more. What does this

tell us about the graph

of the original function? Try reflecting back the vertical line x = a. you get

the horizontal line y = a.

Superimpose this horizontal line onto the graph of the original function. You

should see that it crosses the

graph of the original function at two or more points. So, if the reflection of

the graph of a function fails

the vertical line test, then some horizontal line passes through the graph of

the function more than once,

and vice versa. This is the horizontal line test. if f(x) is some real-valued

function and there exist some

horizontal line y = a which passes through the graph of f(x) more than once (in

other words, f(x) = a for

more than one value of x), then f(x) does not have an inverse. Thus f(x) = x2

defined everywhere does not

have an inverse because its graph, a parabola open upward, certainly does not

pass the horizontal line test.

The graph of the absolute value function does not pass the horizontal line test,

and neither does any of the

trigonometric functions , so none of these functions have inverses. If we

restrict these functions to smaller

domains, however, as we did by restricting f(x) = x2 to the non-negative

numbers, then these function may

have inverses on these smaller domains. This is, for example, how we define the

inverses of the trigonometric

functions, which you will study in detail next term.

| Prev | Next |